Unfortunately am into this rust thing now.. there is no going back, lets learn this mf.

Intro | notes to me#

Rust is a compiled programming language like go | C | C++, to add more in rust memory management is manual unlike

go | java | js etcc, where you will get automatic GC on ur runtime.

In Rust there is a in house tool called cargo, which is the dependency manager, similar to npm in js, cargo new project

creates a new project with directories src/main.rs, cargo.toml files, cargo.toml files contains the project

information like project_name, dependencies needed etc.

- cargo build - builds your program and puts the executable under

target/debuge/*. - cargo check - builds your program and checks if there are any issues, but it won’t produce any binary/executable so its fast compared to build.

- cargo run - builds and produce an executable and also runs the executable for us, similar to

go run main.go

fn hello_world() {

println!("Hello World!");

}

fn main() {

hello_world();

}

Above is the basic Hello world program in rust, as you can see in rust function is declared using fn keyword,

one interesting thing i found is instead of normal println here we are calling println!, the !

means we are calling a macro(kinda c macro) not a normal function.

Crate#

Crates in rust are kinda of dependencies/npm packages in binary or library, that we can use in our application, these can be downloaded using cargo(package manager).

Variables and Mutability#

Any Variables that u declare in rust, by default it is immutable, this has lot of advantages.

- Safety, devs will know for sure this variable will not be changed for any reason.

- Easier for compilers to do optimization, since we know the exact size and the reason that its not going to change.

- Also used for concurrency, many threads can easily read the same variable, coz no one can edit it.

with the above advantages, of course we can define mutable variables as well with the keyword mut.

fn main() {

// let name = "Manikandan";

// println!("Name => {name}");

// name = "Manikandan Arjunan"; // this is not possible in rust by default, since it is immutable, we need

// to add mut in line 2 variable declaration

let mut name = "Manikandan";

println!("Name initialize => {name}");

name = "Manikandan Arjunan"; // this is not possible in rust by default, since it is immutable, we need

println!("Name after update => {name}");

}

Constants#

Constants are similar to variables but will have immutable by default and cannot be changed.

Nthg complex, just same constant that we learned in JS, C, Go etc, mut is not allowed to declare when using

constants.

Shadowing#

Shadowing is basically redeclaring the same variable again, something like below, i guess

rust has this feature so that devs can feel the mutability without using the mut keyword.

not sure this is basically breaking the fundamental point that rust is solving => optimization.

Update:

- I was Wrong here, my initial concern for shadowing is for increasing compiler work by doing more on allocating and deallocating memory often, i tested this, the rustc is way more optimized to do these task faster.

fn main() {

let age = 12;

println!("Before shadowing: {age}");

let age = "Manikandan"; //invalid i know, but this is shadowing, technically

// i can mutate a value without mut keyword either with same type or different

println!("After shadowing: {age}");

}

Datatypes#

Rust is a strongly typed language, meaning the compiler should know the type of any variable, usually rust compiler knows a variable type by its value or the type that is defined(this is needed, when u convert one variable to another etc)

fn main() {

// explicit typing, since we are converting from one to another.

let age: u16 = "27".parse().expect("Not a age");

// implicit typing, rust compiler will know the type name on compile time.

let name = "Manikandan Arjunan";

println!("{age} {name}");

}

Types of datatypes in rust:

Scalar - These are individual types which represent a single value or fixed size value like

Integer,Float,Bool,Char- Integer - Everyone knows this,

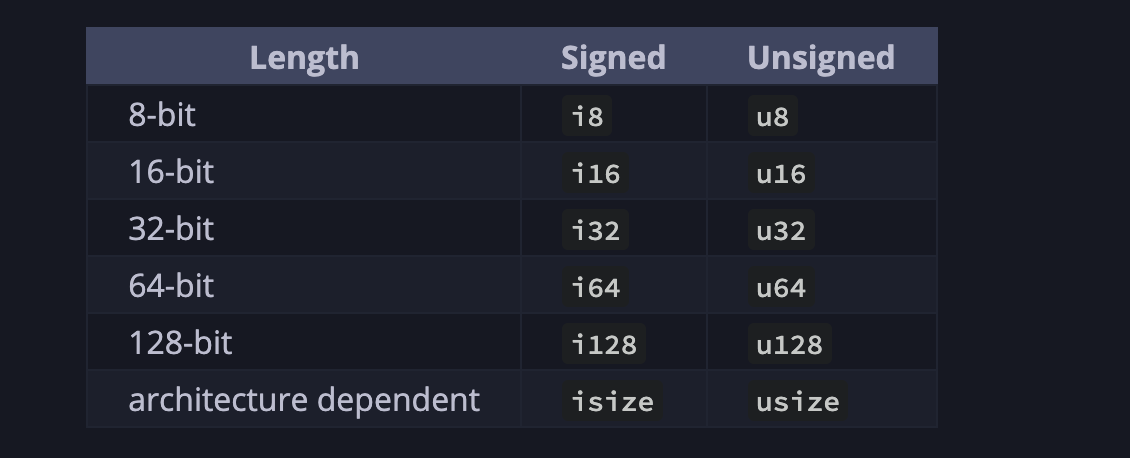

Integeris a type which includes only integers(no fractions), it also hassigned(+ve and -ve) andunsigned(only +ve), Below are the different integer types that rust has, by default if u do something likelet age = 21;, by default rust compiler allocatesi32

- Floating Point -

Floatis basically fractional/decimal numbers. - Boolean -

Booleanrepresentstrue|false.

let t = true; // implicit compiler knows the type let f: bool = false; // with explicit type annotation.- Boolean -

Booleanrepresentstrue|false. - Char -

charrepresents a single character which is of 4bytes, unlike 1 byte in c language, this is coz it supports more characters like ascii, emoji, japanese etc..

- Integer - Everyone knows this,

Compound - Compound types are basically a group of values with one specific types, EG: Array, objects etc.

- Tuple - Tuple type is basically a grouping number of values with variety of types, kinda array but not.

fn main() { let tup1: (i16, char, bool) = (2, 'M', false); let (x, y, z) = tup1; // kinda destructuring in compare with js world. println!("{x} {y} {z}"); println!("{}", tup1.0); // this is also possible }- Array - As we know

arraytype is basically collection of values but with same type(unlike other dynamic language), also in rust array size is fixed by default.

fn main() { let arr: [i16; 5] = [1, 2, 3, 5, 6]; // this is one way of declaring array [i16-> type; 5 -> // size] let arr = [1, 2, 3, 5, 6]; // this is another way of declaring array, where the size // and type are determined by the compiler. let arr = [3; 5]; // this is another way of initializing where if u want to repeat a // specific number with n times, in this case number 3 for 5times. println!("{}", arr[0]); }

Functions#

Functions are similar to everyother programming language, with some minor tweaks, mentioned in the below code

// params as usual specify type, for return type use -> arrow operator

// fn add(x: i16, y: i16) -> i16 {

// return x + y;

// }

// if u see below i have not included semi colon, this is intentional

// x + y is basically an expression so it returns(similar to () => 1 in js)

// if u include semi colon x + y; this becomes statement, so rust returns default

// value () empty tuple

fn add(x: i16, y: i16) -> i16 {

x + y

}

// fn is the keyword, main is the default function that rust calls automatically on any file

fn main() {

add(1, 2);

println!("Hello, world!");

}

Ownership#

Ownership is pretty important concept in rust, this basically explains on how rust deals with memory

management without Garbage Collector or managing manually.

Generally in programming languages there are two ways to manage memory, one is through garbage collection(

JS, Python, Golang etc), another one is through manual(C, C++ using malloc, calloc, free etc),

but rust deals with managing memory in a brand new way called Ownership/Borrowing.

Ownership => A set of rules that the compiler check, if any of those rules are violated, program won’t even compile basically.

Before going into this Ownership, lets understand some fundamental things about stack and heap,

understanding this is important to understand rust model of managing memory.

Stack and heap:

- Stack: Stack is a fixed size of memory that each programming

language(program/application) gets when starts.

- Go: 2KB - 1GB as it grows.

- C, Rust: 8MB

- Javascript: 1 - 2MB

Whenever you write a code and compile it(even js compiles), ur actual code(binary | actual in case of js)

will stays under text | code memory, all your fixed size variables like int, char, etc stored under your stack memory.

Consider the below C code

void callFun2() {

int age = 30;

return;

}

void callFun1() {

int age = 20;

callFun2();

}

int main (){

int age = 10;

callFun1();

return 0;

}

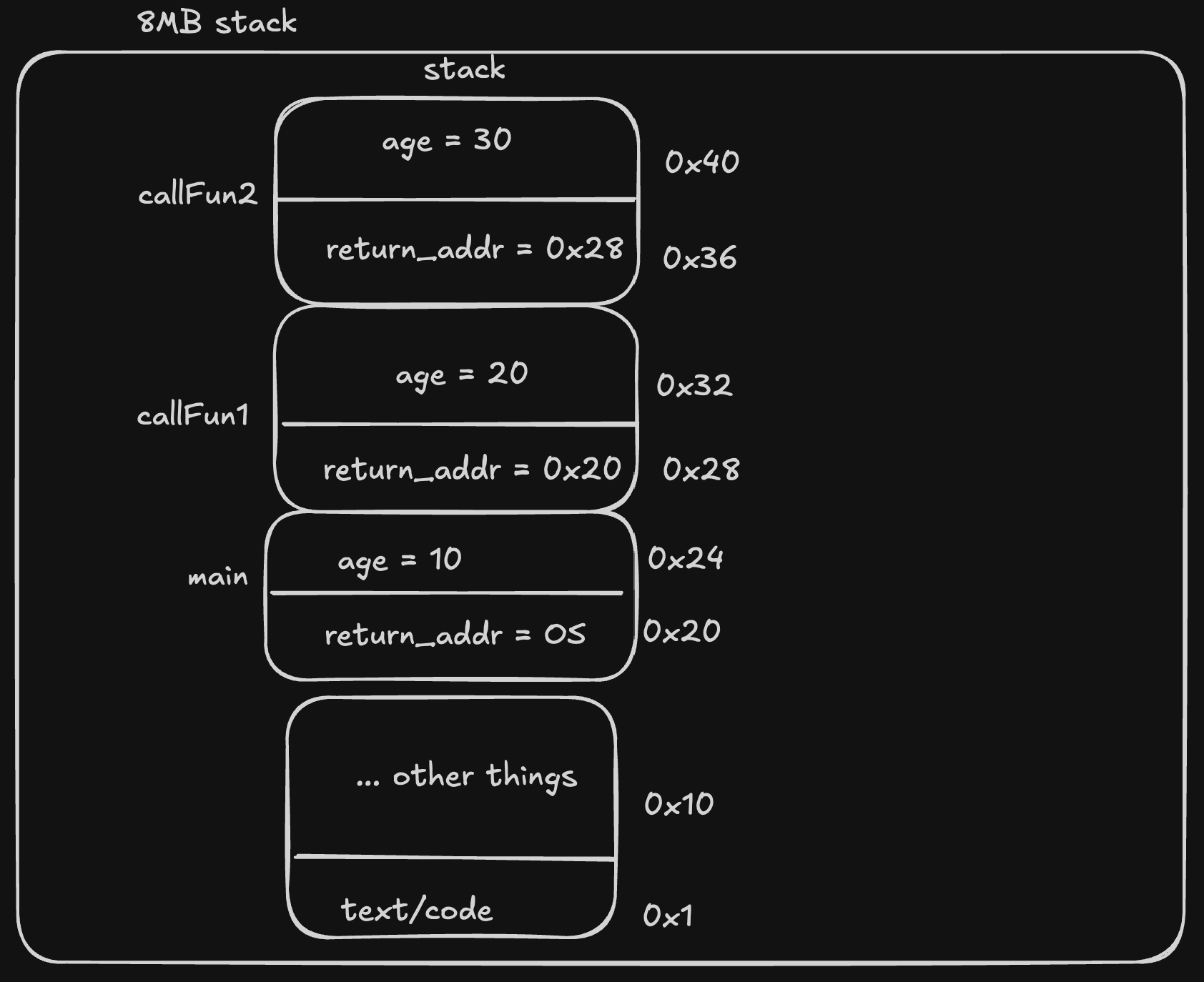

Once u compile and executes(the binary) the above c code, the first function main get pushed into the stack and all its local variables,

inside the main we are calling a function called callFun1, now this callFun1 is pushed on top of stack and its variables

now callFun2 is pushed coz its been called inside the callFun1, once callFun2 is executed

it gets popped off and returned to the calling function(in our case callFun1) using return address and this process repeats

untill its return to the OS(main function returns to OS).

Now you may have a question, whats the limit for this stack size, is it infinite or whole computer's memory or what?

the answer is each programming language gets a fixed stack memory size(these are contiguous) for each program/code that you

executes, whenever you go beyond these language specific memory stack size, you generally get `stack overflow` errors

This usually happens if u have tooo much nested calls and lot of variables(typically seen in non-exited recursive

function). Below are some of the stack sizes of popular programming languages:

- Go: starts from 2KB - 1GB(meaning initially it has 2KB, based on the function calls, compiler scales the stack memory).

- C, Rust: 8MB

- Javascript: 1-2MB

NOTE: All your source code and other stuff lives in different area called `text/code memory`.

in stack only ur function return address variables etc are stored. thats why this MB or KB level

of memory is more than enough for any level of programs.

Another NOTE: Since these stack memory are contiguous, its way faster to lookup and clear this memory.

for eg: lets say u wrote a C code and executing it, ur program will get 8MB of contiguous memory not random.

There is no need for anyone to look after the things(variables) to delete when its not getting used.

Below is minimal stack representation for the above C code.

Fun Fact: There are things like "Closures" in javascript or go or even rust, stores some things in heap

instead of stack, even for primitive variables. Eg: below

function a () {

let x = 0 // closure stored in heap, instead of stack

return (y) => {

return x + y

}

}

// go

func temp() func(int) int {

x := 0

return func(y int) {

return x + y

}

}

- heap: Heap is used to store dynamic/unknown/growing things, which u can't know the exact memory size on

whether it grows or shrinks, eg: dynamic arrays(slices, vectors), hashmap, objects etc.

Its difficult to clean heap rather than stack, coz heap memory is random, OS gives u the free

memory address and its the application responsibility to use it and clean,

in stack when the function popped off, all its things will be popped off(cleared), but

in heap, u need to manually clear from your application end.

C - Its manual, `free` will free the heap memory, malloc, calloc etc gives the memory from heap via OS.

Go, JS, Python etc - Its automatic, the compiler or the runtime has something called "Garbage Collector",

which automatically cleans and provides you the memory, so your application don't need to maintain anything

manually.

The job of this Garbage Collector is to keep track of all the things that are in the heap memory

for a particular program(process) and then clears periodically

if its not been used/referenced by anything in that program.

From the above understanding on stack and heap, we can conclude that in any programming language, u only need to

concentrate on things to be cleared that are in the heap not on stack, stack memory gets popped off

automatically when function complete its execution, for heap, either it should be manual or

language needs to implement something called Garbage Collector and include it in the language runtime.

lets proceed with rust ownership now. the basic rules of rust ownership are

- Each and every value in rust has an owner.

- There can be only one owner at a time.

- When owner goes out of scope, the value will be dropped.

Lets take string datatype in rust to illustrate this ownership example, coz strings are stored on heap

since we don’t know the exact size of those datatypes, btw when i meant string datatype, i was referring

to String namespace declaration not by using literals(these are fixed size and can live in stack), EG Below

let str = "Manikandan"; // this is a string literal and it literally has 4 * 10 bytes of memory.

let str2 = String::from("Manikandan"); // this is string will be stored under heap, where String

// is kinda namespace from standard libray, from that we are using a function called from.

// Since in string literals, we know the exact bytes at compile time, so we can stuff this into our

// stack memory itself, we don't need heap memory for this.

Consider the below code

fn main() {

let str = String::from("Manikandan")

println!(str)

}

If u see the above code, when u declare str, its memory is allocated to heap, and its our responsibility to clean

our means that application owner(manual) or the language(using GC or anyother way)..

In rust this is done via something called Ownership and also something called drop(kinda free from c/c++),

if somethings goes out of scope.

Now consider the below example

fn main() {

let str = String::from("Manikandan")

{

let str2 = String::from("Arjunan")

println!(str)

println!(str2)

}

println!(str)

println!(str2) // error during compile time

}

in the above example, if u see the last line println!(str2), actually this won’t or shouldn’t work

the variable str2 is declared inside the curly braces {} scope, once rust compiler sees the },

it immediately calls drop(&str2), so the last line is not even possible.

Another example

1: fn main() {

2: let str = String::from("Manikandan")

3: {

4: let str2 = str

5: println!(str) // error, coz rust compiler marked str as invalid, since the owner has been transferred.

// of str is transferred to str2.

6: println!(str2)

7: }

8: println!(str) // error

9:}

in the above example, we are defining a string str and then assinging that to str2 on line 4, since str

is not a primitive datatype, copying str to another like this way str2 = str, will only copyies its pointer,

as all languages this won’t copy the exact value, instead this copies the pointer from str and points to str2,

the same happens to rust as well, but the only key difference in rust this type of copy is called Moving the Ownership,

as soon as the rust compiler sees any ownership has been transferred to another in our case str2 = str,

it makes the previous variable in the above case str kinda invalid.

the last will throw error at compile time.

fn main() {

let str = String::from("Manikandan")

{

let str2 = str.clone()

println!(str)

println!(str2)

}

println!(str)

}

the above code, works, coz .clone() basically will copy the exact data(“Manikandan” in our case) and puts

it into str2, so rust compiler doesn’t need to mark str as invalid after the line str2 = str.clone(), coz

there is no ownership transfer

Another example

fn main() {

let str = String::from("Manikandan"); // str is declared and allocated in heap

takes_ownership(str); // passing(in rust terms "moving") the value to takes_ownership function

// str becomes invalid

println!(str) // error

}

fn takes_ownership(some_string: String) { // some_string comes into scope

println!("{some_string}");

}

in the above one, you can see we are basically passing str from main to takes_ownership function

basically moving the str from main to takes_ownership, as soon as we call takes_ownership,

the rust compiler decides the str ownership now has been transferred from main to takes_ownership function

after the function call takes_ownership(str) the str would be invalid, after this line takes_ownership(str)

you can’t literally use str in main function.

If you want to use that str again in ur main function, either u need to return the moved str from the takes_ownership

as i shown in the below code, but this will be an headache, coz u dont want to pass and return everytime,

there are ways to avoid this, which we can see later below.

fn main () {

let str = string::from("Manikandan"); // str is allocated to heap

let str = takes_ownership(str); // the above str will be marked as invalid and a new str will be allocated from the

// return value of "takes_ownership", since rust have the ability to create same variable name its possible

// to bind in str itself

println!(str)

}

fn takes_ownership(some_string: string) -> string {

return some_string

}

more example comparing rust and other languages

fn main() {

let str = String::from("Manikandan"); // str is declared and allocated in heap

takes_ownership(str); // passing(in rust terms "moving") the value to takes_ownership function

// str gets invalid

println!(str) // error

}

fn takes_ownership(some_string: String) { // some_string comes into scope

println!("{some_string}");

}

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

custom_map := make(map[string]int)

custom_map["age"] = 1

print_map(custom_map) //above custom_map won't be dropped/invalid, coz it is available on

// below line if u see, there is a dedicated GC on every go run time binary

// which tracks and delete if its not referenced by any, same follows for JS, python

fmt.Println(custom_map)

}

func print_map(cus_map map[string]int) {

fmt.Println(cus_map)

}

From the above example even rust could implement the same as go, but it comes with a cost, u need to implement ur own language garbage collector, which u need to attach on ur every binary executable etc. to avoid these and also to avoid manual memory management(which is difficult if the program grows), rust tried to comes up with a brand new way of managing/maintaining the memory. imo its amazing for me Rust is the first language to come up with this kinda of solution to manage memory.

References#

If you want to use that

stragain in ur main function, either u need to return the movedstrfrom thetakes_ownershipas i shown in the below code, but this will be an headache, coz u dont want to pass and return everytime, there are ways to avoid this, which we can see later below

as this stated above, in order to prevent this, we can also pass a variable with a reference(borrowing), instead of

moving that variable, we can pass the reference.

NOTE: if u pass the reference, rust compiler won’t call drop/mark as invalid, coz the ownership is still with u. EG: below

Some borrowing rules:

- You cannot create more than one mutable reference/borrow.

- You can create multiple immutable reference/borrows.

- You cannot create one mutable and another immutable reference/borrow.

fn main() {

let str = String::from("Manikandan");

print_name(&str); // str won't be invalid, coz u are moving only the reference

println!(str);

}

fn print_name(str: &String) {

println!("{*str}") // even if u use println("{str}"), rust still prints

// Manikandan, its coz prinln! macro implemented in a way to dereference and print

// if its a reference

}

Use-cases on when this references(borrowing) will be useful

case 1:

fn main() {

let str = String::from("Manikandan");

print_name(&str);

println!(str);

}

fn print_name(str: &String) {

println!("{str}")

}

if u want to pass ur variable to a function only to read, in this case u don’t need to transfer the ownership, these cases are exactly suitable to use borrow instead of transferring the owner.

case 2:

fn main() {

let mut str = String::from("Manikandan");

println!(str); // Manikandan

modify_str(&mut str);

println!(str); // Manikandan Arjunan

}

fn modify_str(str: &mut String) {

if str == "Manikandan" {

str.push_str(" Arjunan")

}

}

if u want to pass ur variable to a function only to read and also to modify, these type of cases u can transfer a mutable reference so that the external function can read and do modifications

NOTE: you can only create single mutable reference, rust is deliberately did this at compile time, to avoid race conditions(where multiple mutable varibles modify the same stuff), however u can create n number(immutable/normal references).

Like the above there are many cases

- if u want to share read only access to many external functions.

- to avoid copying/moving large string. ……

Slice Type#

We have talked about string literals let name = "Manikandan" many times above, basically

all the string literals are one of slices and it has a type called &str string literals

are immutable and also &str type is also immutable.

- String == &str, all String types when we dereference(

&) it will match&strtype, these are all immutable.

fn first_word(words: &str) -> &str {

let bytes = words.as_bytes();

for i in 0..bytes.len() {

if bytes[i] == b' ' {

return "Hello";

}

}

return "Manikandan";

}

fn main() {

let mut str = String::from("Hello HiHas");

let word = first_word(&str);

str.clear(); // Error

println!("{}", word);

}

In the above example if u look, we are passing &str(which is the reference of our str String::from(“hello ..”))

into first_word and the return type of first_word is also &str, in other programming languages its basically means

input &str is different return type of first_word is different reference, but in rust its not,

rust compiler automatically thinks the input to first_word is an immutable reference to str(String::from()),

and the return type of first_word also is an immutable reference of str(String::from()),

even though am returning Manikandan | Hello, rust compiler doesn’t care.

coz of this we are again calling str.clear() clear basically take mutable reference, which exploits our

borrowing rule, where one mutable and one immutable reference is not possible.

TL;DR - Rust basically checks the function signature, and notice that u are passing a reference and returning the same reference, so the function signature return value is an immutable reference.

fn first_word(words: &str) -> u16 {

let bytes = words.as_bytes();

for i in 0..bytes.len() {

if bytes[i] == b' ' {

return 1;

}

}

return 2;

}

fn main() {

let mut str = String::from("Hello HiHas");

let word = first_word(&str);

str.clear(); // no Error

println!("{}", word);

}

no error on above coz the rust looks the function signature fn first_word(words: &str) -> u16,

it sees ok return type is u16, even though input param is taking reference of String, as soon as the function

exits reference of String is of no use, so as soon as this line is executed first_woord(&str),

rust immediately knows &str(immutable String reference) is no longer used.

Structs#

Structs are kinda objects that you can think of(from JS/python perspective), in rust

structs are nothing but a collection of different datatypes into a single entitiy similar to tuples,

the only difference is, in tuples, the order is maintained and also u can’t have any names

for EG let tup: (i16, f16) = (1, 1.0);, in this there are no names for int or float also the

order should be maintained, but this is not true for struct.

struct User {

name: String,

age: i16,

}

To use a struct that is defined, just create an instance using the name of the struct that we defined, and also by providing values to all the properties that we defined.

let u1 = User {

name: String::from("Manikandan"),

age: 21,

}

To get a specific value, you can use dot(.) notation.

println!("{}", u1.name); // this will print Manikandan

You can also edit individual properties/fields if its mutable, the entire instance should be declared as mutable, not individual properties/fields.

let mut mutableU1 = User {

name: String::from("Manikandan"),

// mut name: String::from("Manikandan"), // this is not possible

age: 21,

}

println!("{}", mutableU1.name); // this will print Manikandan

mutableU1.name = String::from("Manikandan Arunan")

println!("{}", mutableU1.name); // this will print Manikandan Arjunan

you can also update one struct from another struct.

let u1 = User {

name: String::from("Mani"),

age: 21,

};

let u2 = User {

age: 22,

..u1

}

NOTE:

- In the above example, u1.name is

non-primitive, therefore it is moved to u2. sou1.name is not accessible after u2.

struct Employee {

name: String,

age: i16,

}

fn main() {

let emp1 = Employee {

name: String::from("Manikandan Arjunan"),

age: 27

};

println!("{}", emp1.name);

println!("{}", emp1.age);

let emp2 = Employee {

age: 28,

..emp1

};

println!("{}", emp1.name); // this won't work

println!("{}", emp1.age);

}

Methods#

Methods are similar to function, exactly like functions, only difference is the functions that are defined in structs(or enums or traits) is often called as methods[implement interface in terms of go]. EG below

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Rectangle {

width: u16,

height: u16

}

impl Rectangle {

fn area(&self) -> u16 {

return self.width * self.height;

}

}

fn main() {

let r1 = Rectangle {

width: 10,

height: 20,

};

// you can also call r1.area like `Rectangle::area(&r1)` this is kinda static method

// in terms of oops.

println!("Area: {}", r1.area());

println!("After value width: {}", r1.width); // this only works coz we have

// borrowed rectangle as &self, normal self also works, but it transfers the ownership

}

Enums#

Similar to structs enum are like constants, that defines a set of possible values.

enum HttpMethod {

GET,

POST,

PATCH,

}

fn main() {

handleRoute(HttpMethod::GET)

handleRoute(HttpMethod::POST)

}

fn handleRoute(httpMethod: HttpMethod) {

}

In the above, if u can see HttpMethod enum takes a list of HTTPMETHODS, that our

simple code supports, this enum also serves as a kind of custom data type for

handleRoute.

Similar to structs, enum also supports methods where methods can implement any enums.

#[derive(Debug)]

enum Message {

Quit,

Move { x: i16, y: i16 }, // enum also supports values to be provided

Write(String),

ChangeColor(i16, i16, i16),

}

impl Message {

fn call(&self){

println!("{:?}", self);

}

}

fn main() {

let m = Message::Write(String::from("Hello"));

println!("{:?}", m); //print Write("Hello")

}

Option Enum#

Option enum is built in with rust standard library, means a value could be something, or nothing.

EG: consider an array with values, if you request for the first item, you will get the value,

consider an array with 0 values, if you request for the first item, you will get nothing.

expressing both of this behaviour is possible via Option enum, in rust there is no concept of

NULL values, as you seen in other programming languages.

Almost all languages have NULL values described as nil, null, undefined etc, this can be error prone

on run time, coz we don’t know if there is a value or null, but rust on the other hand follows a different

approach, basically it says there can be value or nothing and we need to handle both using something like

Option.

enum Option<T> {

Some<T>

None

}

As you can see above, an Option can only have value(Some) or nothing(None).

let x: Option<i16> = Some(1)

let y: Option<i16> = None

in the above variable x contain either i16(1) or None. Now y is None, now you may have question

why not let x: i16 = 1, this is perfectly valid, but not all values can be defined from compile

time itself, how about getting some value from an api or file etc,

in these scenarios, there is no guarantee that we will have i16, in these cases

Option can be useful.

Match with option#

Rust has another powerful control mechanism called Match, can used along with Option enums,

match allows us to compare a value aginst a series of patterns and then execute the matching one.

EG:

enum HttpMethod {

GET

POST

PATCH

}

fn handle_route(http_method HttpMethod) {

match http_method {

HttpMethod::GET => {

// handle get method

},

HttpMethod::POST => {

// handle post method

}

}

}

fn main() {

handle_route(HttpMethod::GET)

handle_route(HttpMethod::POST)

}

EG 2:

enum IP {

V4

V6

}

enum HttpMethod {

GET(IP)

POST

PATCH

}

fn handle_route(http_method HttpMethod) {

match http_method {

HttpMethod::GET(ip) => { // this is also possible, pass another enum into an enum and handling via match

// handle get method

},

HttpMethod::POST => {

// handle post method

}

}

}

fn main() {

handle_route(HttpMethod::GET(IP::V4))

handle_route(HttpMethod::POST)

}

Match and Option, goes hand in hand, as discussed about an option is either a value present or not present,

we can handle all these using Match statements.

EG:

fn main() {

fn plus_one(x: Option<i32>) -> Option<i32> {

match x {

None => None,

Some(i) => Some(i + 1),

}

}

let five = Some(5);

let six = plus_one(five); // also not possible to pass 5, coz 5 is i16 not Option<i16>

// Option<i16> is either Some(i16) or None

let none = plus_one(None);

println!("{:?}", six);

println!("{:?}", five);

println!("{:?}", none);

}

Control flow with if let and let else#

In some Some() value cases, we don’t specifically deals with all the matches using match statement.

fn main() {

let config = Some(3u8);

match config {

Some(max) => println!("{}", max),

_ => (),

}

}

In the above if u see, we have added _ => () this line, coz for Option we need to handle both Some and None

if either of these are unused we need to add _ => (), instead of adding this dummy in order to satisify the compiler

we can use if let pattern, something like below

fn main() {

let config = Some(3u8);

if let Some(var) = config {

println!("{}", var),

}

}

Packages, crates and modules#

- crates – crates are the most fundamental or smallest unit in Rust.

All this time we were dealing with single-file Rust programs;

all of these are called crates, There are two types of crates

- Binary crates - These are executable crates, for eg: you have a rust file with

mainfunction, you compiled and shared the executable directly. - Library crates - These are non-executable, it won’t contain

mainfunction. for EG:randfunction that we used.

- Binary crates - These are executable crates, for eg: you have a rust file with

TL;DR - In simple terms, crate in rust often means library.

- package - packages are a bundle of crates, for EG: when u do

cargo new TEST-PROJECT, this TEST-PROJECT is now a package, as u can see that name incargo.tomlfile, for eg: in this TEST-PROJECT we generally havesrc/main.rsas default, this will be one crate(binary crate, coz when we do cargo build, this will be compiled to a bin)

we can also define crates inside cargo.toml file, if there is no file defined, by default file src/main.rs will be

the binary crate and src/lib.rs will be the library crate.

Some rules of crates#

- a package must have atleast one crate(either library or binary).

- a package can have either 0library crate or 1library crate, not more than that.

- a package can have multiple binary crate.(multiple binary crates can be placed under

binfolder)

Modules#

Modules are part of crate, a file is basically a crate, inside u can have many modules. For EG:

// user.rs // this is crate

mod User { // this is module

pub mod Details { // this is submodule

fn get_name() {}

}

}

// you can access the above in other file by declaring the module name

mod user;

use user::User::Details

fn main() {

get_name()

}

// you can also define module/submodule in same file or different file.

// for EG:

user.rs

mod temp // this should come under user/temp.rs, basically the parent module should be directory and then submodule

// should be file

Collections#

Collections are nothing but some of the very useful data-structures that are already built in the std-library like stack, queue, hashmap, vector etc.

Vectors#

Vectors are just dynamic array in rust.

fn main() {

let normal_arr: [i16; 5] = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; // normal fixed size array, on stack memory,

// meaning the size is determined on compile time itself, so this main stack can allocate

// memory according to that, u cannot shrink or grow this size.

for i in normal_arr {

println!("{i} \t");

}

let mut vec_arr: Vec<i16> = Vec::new();

// let vec_arr = vec![1, 2, 3]; this is another way of declaring vector using inbuilt macro

// vec!

vec_arr.push(1);

vec_arr.push(2);

vec_arr.push(3);

vec_arr.push(4);

let first = vec_arr[0];

println!("First element of vec_arr => {}", first);

let mut vec_arr_2: Vec<String> = Vec::new();

vec_arr_2.push(String::from("XXXX"));

vec_arr_2.push(String::from("YYYY"));

vec_arr_2.push(String::from("ZZZZ"));

let first = vec_arr_2[0]; // this will throw error, coz considering the rust borrow and

// ownership concept, when we assign vec_arr_2[0] to first, we are basically

// transferring/moving the ownership which basically means moving out of the vec_arr_2,

// in the above vec_arr[0] you won't get the same error, it is bcoz above vec_arr is using i16

// which is a primitive type,

// to fix this vec_arr_2[0], you either need to read as reference &vec_arr_2[0] or do

// vec_arr_2[0].clone() which clones a new one and assigns to first

// NOTE: println!("{}", vec_arr_2[0]) works without & or clone, coz by default

// the inbuild println! methods does add reference operator & when needed

println!("First element of vec_arr => {}", vec_arr_2[0]);

}

Below program on how vector can be accessed without any issues

fn main() {

let vec_arr: Vec<i16> = vec![1,2,3,4];

// println!("{}", vec_arr[20]); // this will result array out of index panicing(u know the

// reason), this is usual in every languages, but in order to access an invalid index

// value without crashing the program rust provides a method called "get" where it will

// return Option<T>, so u would end up in None if that index is not accessible

match vec_arr.get(20) {

Some(twenty) => println!("{}", twenty),

_ => println!("Index is out of range")

}

match vec_arr.get(1) {

Some(one) => println!("{}", one),

_ => println!("Index is out of range")

}

// NOTE: by default [Vec::].get() will returned referenced value(&)

}

Below program u can see the mutability rules for vector(nothing special, just the same)

pub fn main() {

let mut vec_arr: Vec<String> = vec![String::from("XXXX")];

let first = &vec_arr[0];

vec_arr.push(String::from("YYYY")); // this won't work coz we already created one immutable

// reference vec_arr[0] and assigned to first, now when we do vec_arr.push

// the push underlyingly creates mutable reference to this vec, coz it may needed to increase

// the array length if its already full or delete coz of this it may need to shift all the

// elements the indexes can change, the immutable reference above can become invalid.

// to make this work either create copy .clone() and assign to first, or move this print

// to above the line, so that the immutable scope destroyed.

println!("{}", first);

}

Strings#

Strings in rust are just a collection of UTF-8 bytes stored contiguously(in vector prbably something like Vec means unsigned 8bit(1byte)), to read about UTF-8 click this

fn main() {

let mut hello = String::new();

let world = "world"; // string slice &str

hello.push_str("Hello"); // u can push new strings into a String using push_str

hello.push(' '); // u can also push single character using push method

hello.push_str(world); // u can also push string slices(&str)

hello.push('!'); // u can also push single character using push method

// let first_char = hello[0]; //this is basically not possible in rust, unlike other langugage

// coz rust supports utf8 encoding characters, in our above example hello[0] can

// print naturally H, but consider different language, where a single letter could take

// multiple bytes, in those scenarios the result would be very different.

// for EG

// let russian_hello = String::from("Здравствуйте");

// let first_char = russian_hello[0];

// in the above example russian_hello[0] is not going to be 3, it could be something else

// infact the length of this string stored in rust underlying is also 24 and not 12, coz

// of how utf-8 encodes each unicode into bytes, in order to resolve this

// u can use [String::].chars() function where u will get each characters, u can also

// use [String::].bytes() to get the raw bytes

for c in hello.chars() {

print!("{}", c);

}

println!("{}", hello);

// NOTE how this works in other languages

// Python

// python first reads all the characters in the string and takes the largest unicode byte

// character and make the character byte length as their individual element length for the

// array for EG: "mani😀", here actual byte of this string is 8 bytes m-1, a-1, n-1, i-1, 😀-4,

// python takes the largest character unicode 4byte which is the smiley and then assigns the

// same across this array something like below

// [4byte, 4byte, 4byte, 4byte, 4byte]

// why -> easy to iterate and then length is also same and whenever u do [0] | [1] etc u will

// get the exact character

// Javascript

// js by default takes 2bytes to store every character in a string. for the above example

// it stores like [2byte, 2byte, 2byte, 2byte, 2byte, 2byte]

// if u notice our array length is of 6, its coz to store smiley u need extra 2byte, so it

// took another character in our array, in js for this example when u do arr[4] u will get some

// random unicode instead of smiley, but in python u would get the smiley.

// Python tradesoff the space, js tradesoff smileys(lol)

// in js if u have const str = "mani😀js", if u do str[5] instead of js u will get something else(some

// part unicode of that smiley), but in python if u do str[5] u would get "j"(u know the reason now)

}

Hashmaps#

Hashmaps are key value pairs(object literals/Map in js), HashMap<K, V> where k is the value and v is the type of

that value

use std::collections::HashMap;

fn main() {

let mut persons_age: HashMap<String, i16> = HashMap::new();

persons_age.insert(String::from("Manikandan"), 29);

persons_age.insert("test".to_string(), 20);

let test_2 = String::from("test_2");

persons_age.insert(test_2, 10); //move test_2 ownership, after this line test_2 is not

//available

println!("{:?}", persons_age);

let test_to_get = String::from("test");

if let Some(age) = persons_age.get(&test_to_get) { // this is how u can get value by key

// by default get function accepts reference to any variable, even

// for primitive keys u need to pass as reference &, eg below function rank_person_hashmap

println!("{}", age);

}

rank_person_hashmap();

iterate_over_hashmap(persons_age);

}

fn rank_person_hashmap() {

let mut rank_person: HashMap<i16, String> = HashMap::new();

rank_person.insert(1, String::from("Manikandan"));

if let Some(name) = rank_person.get(&1) { // even though it may seem &1 redundant, coz address

// of value 1 is not even valid right, coz 1 is value not a variable to get the memory

// address, but it is what it is that rust is designed to avoid copy/cloning for

// non-primitive things, even for this rust internally does

// let temp: i16 = 1;

// rank_person.get(&temp);

// free(temp)

// something like this

println!("{}", name);

}

}

fn iterate_over_hashmap(map: HashMap<String, i16>) {

for (key, value) in map { // if u are using without reference, this is basically transferring

// the ownership, use it with reference &map

println!("{}: {}", key, value);

}

println!("{:?}", map);

}

Error Handling#

Unlike other programming languages, rust doesn’t have exception handling, rust only has two types of error handling

un-recoverable errors and recoverable-errors.

- un-recoverable errors: logical errors which panic at runtime, like accessing out of bound index value in an array or accessing invalid memory address etc.

- recoverable-errors: file not found error, opening an invalid file etc.

use std::fs::File;

use std::io::ErrorKind;

use std::io::Error;

use std::io::Read;

fn read_from_file() -> Result<String, Error> {

let mut file = File::open("test.txt")?; // ? basically returns error if it encounters error

// when reading a file, if success it will assign the file to file variable, similar to matchotherwise it will

let mut str = String::new();

file.read_to_string(&mut str)?; // same as above if it got any error, it will return coz of ?

return Ok(str);

}

fn main() {

// panic!("App got crashed"); // manually generating unrecoverable error

let file = File::open("test.txt");

let file = match file {

Ok(f) => f,

Err(error) => match error.kind() {

ErrorKind::NotFound => match File::create("test.txt") {

Ok(file) => file,

Err(error) => panic!("{}", error),

},

other_error => panic!("{}", other_error),

},

};

println!("{:?}", file); // above is example for recoverable error

read_from_file();

}